The RSA Conference (RSAC) is over and while there, I had an opportunity to talk to a number of Chief Information Security Officers (CISOs) about their challenges, especially their ability (or inability) to address the almost daily deluge of new cyber security risks. I'm sorry to have to report that at no other time in my memory has the gulf between identifying and responding to risk ever been greater.

ClickToTweet: Keeping CISOs Off The Ledge from Bob Bigman #DefenderOfData http://bit.ly/1GmaJeq

This is not good news and, for many, not surprising. There are many reasons given to explain this expanding gulf. First, and foremost, is the difficulty in trying to secure increasingly more complex Information Technology (IT) assets, both hardware and software. Commercial IT hardware and software contain a bewildering amount of proprietary and open source code libraries that change with every update and version release. Trying to determine which systems may be susceptible to a particular Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) backwards version attack (e.g., Poodle) and then managing the implementation of the remedy can quickly lead a CISO to a “walk on the ledge.” No organization (public or private) keeps an inventory of all their procured system and internally developed code libraries and firmware baselines. For that matter, many well-known network, operating system and application vendors have privately admitted that they do not even know what exactly is in their code/firmware from release to release. Of course they don't since much of today's systems and applications are coded off-shore by the lowest cost programming shop. How can we ever secure our country's critical infrastructure if we don't even know what it is made of? Even if a CISO can be talked in off the ledge and actually finds and secures a particular technical risk in their internal network, what about all the second and third party partners and vendors (think Target Corporation) who have (often routed) connectivity into the internal corporate network; not to mention the outsourced IT as-a-service connections and platforms. Next, mention the Internet-of-Things (a hot topic at the RSAC) and it is back out to the ledge for the CISO.

Related to the issue of technical complexity is the inability for organizations to actually manage their IT assets and data. While organizations have been quick to embrace initiatives like partner/vendor connectivity, outsourcing IT as-a-service and mobile computing, they have not correspondingly increased their IT asset tactical and strategic governance to properly manage the corresponding increased complexity, especially increased security risks. Most CISOs confided that their organizations never actually had adequate IT asset and data governance measures in place even before everything suddenly became “completely unmanageable” within the last 12-24 months. Unmanageable IT almost always means insecure IT. The unpleasant result for the CISO is having to play “catch-up” when they eventually learn of new (or dramatically changed) IT systems/applications, network connections and, in one-story, outsourced code development to a country that is in direct and aggressive competition with the CISO’s organization's primary product.

The next CISO issue that is expanding the gulf between finding/addressing risks and developing/implementing cyber security strategies is the increasing impact of (often conflicting) internal, local, federal and multinational government regulatory requirements. As cyber security risks increasingly threaten both corporate (and now potentially public) well-being, there has been a substantial increase in (often very detailed) cyber security compliance/regulatory requirements. Now add to this mix, new due-diligence requirements from cyber security insurers, and the CISOs are dealing with a (again bewildering) mix of auditor, compliance and regulatory agency demands to enhance cyber security. One of the questions I asked the CISOs was if they are using the NIST Cyber Security Framework to address their cyber security risks. Almost, every CISO answered that they have three or four other regulatory frameworks to address well-ahead of the NIST framework guideline. As internal corporate auditors and lawyers haggle with external “compliance police” over cyber security priorities (and here is where I will mention that most regulators I have met lack sufficient knowledge of cyber security to regulate) CISOs have become mesmerized into inaction. Those who have not become mesmerized have made it out to the ledge.

Lastly, it had become increasingly apparent that many of the promises made by many cyber security product vendors have simply not come true. Most cyber threat intelligence services fail to identify the next malware. Security Information and Event Management products (SIEMs) overload even competent analyst and fail to find the critical nugget needed to stop an attack. Most operating system hardening products (e.g., white-listing) and anti-virus software also fails to stop malware and prevent intrusions. Trying to ensure the correct security configurations (e.g., Group Policy settings) on a global multi-domain network running heterogeneous applications with multiple network entry points has become the proverbial “snipe hunt.” Many CISOs confided that after walking the-too numerous-isles of RSA conference vendor stalls they came away with the perspective that there were very few new answers to their challenges.

Yes, the job of the CISO has become both very complicated and very frustrating. However, all hope is not lost and there are indeed a number of “high-value” initiatives that CISOs can do now (some without much cost) to take back control of their networks and systems that address the frustrations described above. The following recommendations directly address the challenges raised above and greatly reduce the risk of the CISO walking out onto the ledge.

First and foremost, CISOs need to implement deeper and broader tactical and strategic governance measures. Regardless of whether or not the organization’s IT programs follow industry governance best-practices, the CISO can implement measures to “herd the cats.” The CISO should establish both policies and processes to ensure that critical tactical changes to the organization’s networks, systems and applications receive a full cyber security vetting. Even if the organization lacks engineering review boards, the CISO can establish a cyber security engineering review board with a formal charter that mandates which types of activities require what level of review. This measure can greatly reduce the risk that the IT program will enable direct connectivity to a third party vendor (think Target Corporation) without cyber security review. Similarly, the CISO should become actively engaged in the organization’s strategic IT planning process to reduce the risk of surprise. Investing in IT strategic planning can indeed reduce the cost of cyber security mistakes made in implementation.

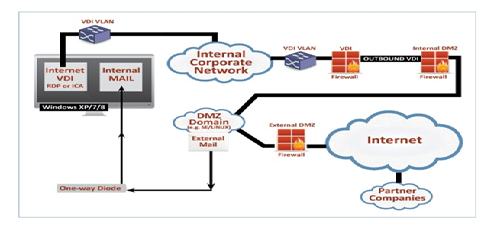

Next, it is time to revisit how organizational internal networks connect to the Internet and second/third party partners and vendors. Given the unmanageable complexity of contemporary networks, the difficulty in patching/hardening systems and the growing recognition that many vendor anti-malware products simply do not work, CISOs need to change how the game is played. Internal enterprise networks demand greater isolation and all connections between the internal network and the Internet and external organizations (i.e., outside the internal address space) should only be established from a secured DMZ domain. External users (including hackers) and partner companies should only be able to access an organization’s data that is available within the DMZ. See the diagram below:

Next, it is time to revisit how organizational internal networks connect to the Internet and second/third party partners and vendors. Given the unmanageable complexity of contemporary networks, the difficulty in patching/hardening systems and the growing recognition that many vendor anti-malware products simply do not work, CISOs need to change how the game is played. Internal enterprise networks demand greater isolation and all connections between the internal network and the Internet and external organizations (i.e., outside the internal address space) should only be established from a secured DMZ domain. External users (including hackers) and partner companies should only be able to access an organization’s data that is available within the DMZ. See the diagram below:

Lastly, organizations need to begin protecting their data as if it was national security sensitive information. Accomplishing this requires multiple steps. First, the CISO needs to review the organization’s data classification policies to ensure that there is unambiguous guidance on identifying and securing sensitive information. Successful companies also provide online tools/guidance to assist their employees in properly classifying sensitive data. An organization’s most sensitive data should only be stored in a network isolated internal subnet and only be accessed by virtual clients that do not allow data movement unless Data Rights Management (DRM) protections are in-place. The most sensitive data should be further protected via encryption (and the keys made inaccessible to the network/system administrators) and a data access control firewall. If sensitive data needs to be shared with partners and vendors, it should either be kept (encrypted and DRM controlled) on the DMZ (described earlier) or kept in the internal subnet and accessed via a highly restricted virtual client installed on the partners or vendors internal network.

The three measures, described above, will go a long way in addressing many of the critical frustrations causing anxiety in the CISO population. By making organizational enterprise networks and sensitive data more secure by design, it reduces the need to continually play the patch and upgrade game to keep track with every new exposure. This approach should also reduce the harangue from the multiple voices of the “compliance police” and internal/external auditors to do more with fewer resources. Establishing an effective cyber security governance process will begin to reduce the “surprise factor” which constantly frustrates today’s CISOs. An effective cyber security governance process also (over time) engenders a broader and deeper relationship between the cyber security program and the IT operations teams building and deploying systems. Integrating cyber security deep into the IT change management process also builds confidence with the compliance and auditing functions. Finding (and then securing) the organization’s sensitive information is a significant step forward towards building a cyber security program that both the auditors and “compliance police” will love and, hopefully, reduce aggressive oversight. Together, these measures will get the CISO more influence (and control) and in off the ledge.