In late October, the U.S. Department of Transportation’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) issued a set of guidelines for cybersecurity in vehicles, intended to provide direction for car makers. According to U.S. Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx, the NHTSA’s aim is “to help protect against breaches and other security failures that can put motor vehicle safety at risk.” The proposed cybersecurity guidance for connected cars focuses on layered solutions to ensure vehicle systems are designed to take appropriate and safe actions, even when an attack is successful.

In late October, the U.S. Department of Transportation’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) issued a set of guidelines for cybersecurity in vehicles, intended to provide direction for car makers. According to U.S. Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx, the NHTSA’s aim is “to help protect against breaches and other security failures that can put motor vehicle safety at risk.” The proposed cybersecurity guidance for connected cars focuses on layered solutions to ensure vehicle systems are designed to take appropriate and safe actions, even when an attack is successful.

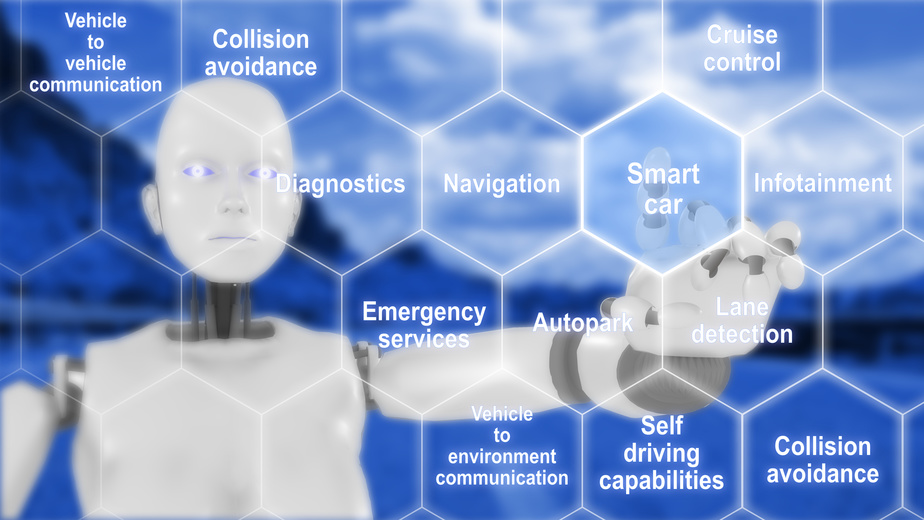

Although the advanced technology found in modern vehicles enhances the driving experience, this increased vehicle complexity also introduces a myriad of new security vulnerabilities and privacy challenges. As we’ve seen many times, attackers can often hack into connected products with shocking ease.

I for one applaud the initiative; it’s great to see the DoT is addressing the growing cyberthreats associated with connected vehicles. However, there are a few key elements still missing from the best practices laid out by the NHTSA. Let’s dive in further to discuss what they got right, as well as additional guidelines that would help to ensure an even stronger security posture for connected cars.

Click to Tweet: Building on #NHTSA best practices for #connectedcar security bit.ly/2fTRJti pic.twitter.com/DiR4ku0bEG

What the NHTSA got right

The following best practices demonstrate progress toward securing connected vehicles:

- Control access to firmware – The NHTSA advised manufacturers to focus on controlling access to firmware, as “extracting firmware is often the first stage of discovering a vulnerability or structuring an end-to-end cyberattack,” creating a big window for trouble. The guideline also notes that disk encryption should be considered to prevent the unauthorized recovery and analysis of firmware.

- Limit ability to modify firmware – Another solid best practice recommended by the NHTSA is to limit the ability to modify firmware. Strong authentication and code signing should be implemented, ensuring only authorized updates can be made and making it much more challenging for malware to be installed on a vehicle.

- Control communication to back-end servers – Additionally, the NHTSA suggests employing encryption methods in any IP-based operational communication between external servers and the vehicle. By using digital certificates to validate connections – often referred to as a “digital handshake” – the communication between the server and vehicle can be properly secured.

What’s missing?

To ensure an even stronger security posture, additional guidelines might include areas such as:

- Control the code supply chain – this means documenting policies and procedures at the OEM level that codify the manufacturer’s cybersecurity requirements. Modern vehicles comprise a large collection of code provided by sub-tier suppliers, so it behooves OEMs to provide instructions about what security protocols are expected.

- Strong authentication for connected components introduced during manufacturing – this would entail injecting cryptographically based digital credentials into each component upon assembly to provide a root of trust. From there, each component’s authenticity can be verified.

- Protecting the manufacturing process itself to prevent the production of unauthorized devices and the introduction of untrusted code – this can be achieved on the factory floor with security controls that ensure the production run includes only the pre-defined number of units and only the pre-authorized software to be installed on each component. Without such controls, a bad actor could remotely modify the production run to process additional units or introduce unauthorized code. Those units could then become trusted parts of the ecosystem unbeknownst to the supplier or OEM.

Conclusion

Overall, the NHTSA’s guidelines are a great first start, especially coming from a prominent industry organization. But with cybersecurity, unfortunately, what we’ve seen in industries across the board is that adequate security is only implemented when required by regulation or other mandate. A logical next step might be for a broader consensus to be built around these guidelines and then elevated to the level of industry mandates, which would require a great deal of support from regional governments. Ultimately, my hope is that connected car manufacturers take action to improve the cybersecurity of their vehicles, and the NHTSA has taken a solid step in driving connected car security forward.

Want to share your perspective on the NHTSA best practices? The public can submit feedback by visiting regulations.gov and searching for docket NHTSA-2016-0104.

Thales | Security for What Matters Most

Thales | Security for What Matters Most