Introduction

Let’s suppose the United States I.R.S. is in the process of chasing down a tax-dodging expatriate and wants access to financial records from a Finnish company the expat has done business with. The U.S. would simply ask the company to fork over the data and all would be copacetic, right?

Wrong.

With more than 99 countries with data privacy laws on the books as of mid-2013 (and a further 21 countries with bills pending), there are wide global variations in requirements for protecting and storing personal data. Regulations range from very strict to more flexible, depending on the country. For example, both Germany and Spain have regulations preventing basic personal information from leaving a legal jurisdiction without explicit consent for each usage. On top of this there both national and regional rules (such as EU Directive 95/46/EC) that specify how personal data must be protected. This directive includes a US “safe harbor” provision that allows organizations to self-certify for data protection requirements. A US based company doing business in Germany, for instance, may be compliant with the “safe harbor” provision for data protection, but still be in violation of the local German privacy regulation when personal data is accessible from outside of Germany.

If multi-national companies want to maximize business efficiencies with the most robust technologies available, it is imperative they understand the numerous challenges posed by the current data residency landscape.

Below, I’ve provided an overview of recent European data residency legal findings, to give you an idea of the technological and legal conundrums many companies face. I also offer advice on a solution for remaining compliant with all data regulations, regardless of jurisdiction.

The Case of Google in Spain

In December 2013, Spain’s Data Protection Agency fined Google $1.2 million for breaking Spain’s data protection laws. Specifically, the DPA cited Google for a) collecting information about its users in Spain sharing that data across its services b) not properly informing them of collection practices.

As of publication, the DPA had struck Google yet again, over “the right to be forgotten.” The complexity of this issue warrants its own blog post, but I think it’s safe to say this won’t be the last clash between Google and European regulatory bodies.

The Cases of Google and Facebook in Germany

In October 2013, German courts took a more business-friendly approach toward business liabilities for data protection violations. The Schleswig-Holstein Administrative Court ruled “companies using Facebook Inc.'s fan pages can't be held responsible for data protection law violations committed by the social networking site because the companies couldn't control the use of the data.”

The ruling overturned an August 2011 order from the Schleswig-Holstein's Data Protection Authority (ULD), which stated companies and public entities using web analytics to measure usage patterns are responsible for enforcing data protection compliance. At the time, the ULD also absolved Facebook of its responsibility to protect data due to the company not maintaining a physical office in Germany.

Google didn’t fare as well as in the eyes of the German court system. In November 2013, the Regional Court of Berlin ruled Google’s privacy policy and terms of service violated German data protection law, stating 13 privacy policy clauses and 12 terms of service clauses were “too vaguely formatted and can restrict the rights of consumers.” Also coming under fire was Apple; in May of 2013 the Regional Court ruled it, too, violated German data protection law. Similarly, 12 clauses in Samsung’s terms of service were ruled invalid by the Regional Court of Frankfurt am Main last year.

At this point, you might be struggling to keep track of all the judicial bodies making privacy rulings. I’d like to say it gets easier from here, but there’s an even more byzantine issue enterprises are grappling with: how data residency applies to the cloud.

The Question of the Cloud

Clearly, varying data residency laws continue to cause headaches for multi-national businesses and governments handling personal data (which includes, among other things, customer and employee data, financial information, data about purchasing habits, etc.) Also adding an extra layer of complication is the proliferation of cloud providers with data centers located in jurisdictions different from those of their customers.

As Computerworld’s Steve Pate has noted, “there is a complex web of regulations and policies that govern data privacy. The most frequently cited are the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), and the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS). European data protection laws often go even further, prohibiting any personally identifiable information from moving outside EU or country borders. This puts some obvious limits on unrestrained use of the public cloud…organizations are also concerned that law enforcement or government officials could potentially access data directly from their CSP, bypassing the company completely.”

Because there are no internationally agreed upon laws around data sovereignty, enterprises seeking to utilize a cloud provider with data centers all over the world are often left asking many questions. Such as, whose laws apply? The laws of the country in which the data originated? The laws of the country in which the cloud customer is based? The laws of the country, or countries, in which the cloud provider houses its data centers?

Making Sense of Data Residency

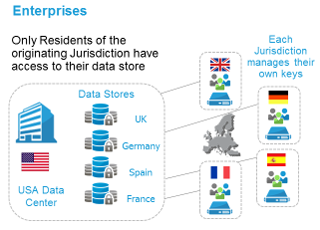

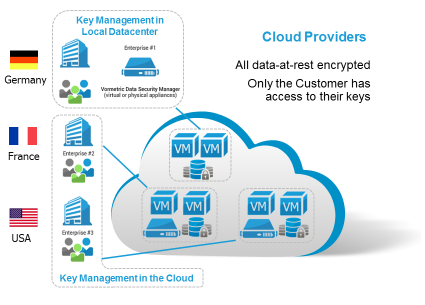

Although the previous discussion may seem to indicate otherwise, it is possible to remain compliant with data residency laws and ensure data is being protected. The best way for companies to make this happen is to ensure all customer and employee data is not be accessible to those outside of their home legal jurisdiction ( exceptwhen explicit consentis give on a per usage basis). How? By encrypting the data and limiting access to onlyusers within a given jurisdiction.

There are numerous solutions on the market for encrypting data and various encryption technology approaches for data at rest. An increasingly popular tactic is tokenization, which we covered in our technical white paper.

Tokenization is the process of replacing sensitive data with unique identification symbols (a “token”) that acts as a proxy for the original information. The original data is kept in a master database that can be hardened, encrypted and keeps track of which token matches which original piece of data. This approach seeks to minimize the amount of sensitive data a business needs to keep on hand and typically is applied to a single field or column (e.g. credit card numbers, social security numbers). By swapping out all the sensitive numbers, most of the data security can be focused on the one system that’s easier to control. Tokenization can be applied inside an enterprise environment or via a service provider.

Tokenization solutions may even solve the problem for SaaS providers by substituting data in ways that allow the SaaS site to function even with the substituted data, while keeping the lookup table matching the “token” against the actual data in the required jurisdiction. And with tokenization, enterprises leveraging public cloud solutions do not need to worry about where the CSPs data center is located, since the actual data never leaves their in-country data center where the tokenization process occurs.

While the myriad laws governing data residency indicate CISO’s and CSO’s have their work cut out for them, it’s more straightforward than you think. Security executives must take the time to understand the data residency conundrum, do their due diligence in researching and understanding encryption solutions that best fit their needs and deploy a solution that allows their companies to stay both compliant and safe. Leveraging data storage solutions in order to maximize business operations while also minimizing regulatory and legal liabilities is entirely possible – it just takes that extra step.